Flying Success at Freshfield, Formby 1910

Reg Yorke 7 May 2010

The Liverpool Daily Post reported at half past three o’clock, just as the sun had risen, the aeroplane arrived on the shore. Within an hour from the time of unshipping it, its parts had been assembled and was ready for the fray. For some twenty minutes or so, Mr. Paterson drove the machine backwards and forwards along the hard, dry sandy beach in order to test the capacity and temper of the engine. Then, to the surprise of the little knot of people present, he quietly and gracefully rose from the earth, and soaring into the air, sailed away for about 100 yards. With the same ease that he had risen, he came down lightly to the ground amid the congratulations of his friends upon what, under the circumstances, must be regarded as a marvellously successful debut. For two or three hours he continued his experimental trials, making upwards of a dozen aerial excursions at varying heights and distances. The longest flight was about half a mile at an altitude of about 30 ft. spoke well for the manner in which Mr. Paterson had built his aeroplane that its balance in the air was so unfalteringly true and perfect. As it rose, its movements were guiltless of the slightest wobble or eccentricity.

Paterson’s plane, which cost £625 to build, had a framework of ash, silver spruce and bamboo. Its weight when the tank was filled with six gallons of petrol – enough for 90 miles – was a little over 600 lb. The 30 hp. engine was a French Anzani. The Daily Post reporter thought the machine ‘picturesque and eloquent of flight’, and was in no doubt that its ‘maiden voyages’ would ‘remain memorable, not alone in local annals, but also in the records of English aeroplaning.’ In all probability, Paterson was the first aviator to fly at his first attempt on his own untried machine.

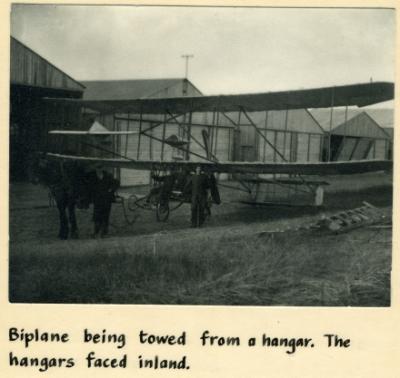

Within a few days of his triumph, Paterson was planning to build hangars at both Freshfield and Southport, but decided to concentrate his activities at Freshfield, where he built three hangars (to one of which he added a bedroom), took extensive grounds,’ carried out experiments and gave lessons!

On 23rd June, Paterson made his second flight. He took off easily enough, but then swerved into the line of sand hills bordering the shore. Wisely, he had strapped himself to his seat and was unhurt. The plane suffered badly; both blades of the propeller were smashed, the wings were torn, wires were broken, and the framework was severely bent. The cost of repairs was put at between £200 and £300. Paterson overcame the fault in his design by fitting a pendulum balancing device of his own invention.

Tests in a gusty wind gave splendid results, said the Formby Times. A review of Paterson’s progress by The Aero does not mention the crash, but says that on 30th July he made some straight flights in a 20 mph. breeze, ‘two of the longest being five miles each.’ He did even better on the following (Bank Holiday) Monday. ‘After flying round for the best part of an hour, making seven or eight-mile flights,’ Paterson heard that an aviator had landed at Southport; at once he determined to meet him. It was Grahame-White, who had flown from the Blackpool Carnival, and whose arrival, according to the Manchester Guardian, drew all the bare-legged population of the seaside towards him like a new Pied Piper of Hamelin. Having travelled the eight miles from Freshfield at 35 m.p.h. and at an altitude of 100 feet, Paterson landed within sight of Grahame-White’s plane, only to find the dense crowd so uncooperative that a meeting was impossible.

Some nine days later, in his hotel at Southport, Paterson was awakened by the noise of another biplane; it belonged to Robert Loraine and was making its way from Blackpool to North Wales. Through his bedroom window, Paterson saw Loraine flying low over the shore, and that the weather was “ideal for a spin”. By mid morning, he astonished Southport people by flying over their cheering heads, across the pier and along the North Promenade, before returning to Freshfield at 50 m.p.h. On the same evening, he flew to Waterloo and back, a round trip of 14 miles.

For a good distance, said the West Lancashire Coast Chronicle, he let go of the steering gear and waved both arms to the people below. At Waterloo, he had a hearty reception from a large concourse of spectators, who flocked to the shore. Mr. Paterson is doing some flying every day. He has marked out several miles along the shore, and flies regularly over these marks, circling, ascending and climbing at will.

The Southport Visiter of 11th August said of Paterson’s aircraft: “When in motion, the biplane is manipulated by one main steering and control column. The work is simplicity itself. By a slight movement of the wheel with one hand, the aeropIanist can work any part of the machine. By the use of one lever he can also control the engine, and he has three different methods of stopping it, so that should the first fail, resort is made to either of the remaining ones. Two mascots in the shape of Teddy bears, presented to Mr. Paterson by lady admirers, accompany him on all his aerial journeys.

On 13th August, Claude Grahame-White again visited the area, on this occasion calling at Freshfield and his subsequent takeoff caused consternation, So powerfully disturbing were the revolutions of the propeller that he covered the bystanders with sand, reported the Chronicle. Shortly afterwards, the following notice was posted: Persons on the foreshore below high-water mark during aeroplane practice are there entirely at their own risk.

Another who came here to practise was Gerald Higginbotham, a wealthy “dare-devil” engineer and motorist from Macclesfield. His chance arrived when he saw a new Bleriot for sale in a Manchester car saleroom. He bought it, towed it home, but could find no field big enough for take-off. As Freshfield had the open spaces that Macclesfield lacked, Higginbotham built another hangar on the shore; and having hitched the dismantled monoplane to his car, set off before daybreak on a fine summer morning in 1910. By 6.30, I had arrived on the sands, reassembled the plane with the help of my four assistants and flown a straight mile. His only instructions were on two sheets of foolscap paper sent to him by Bleriot!

At first, Higginbotham was able to make only straight flights and had to land in order to turn the plane round; but by practising each weekend, he became a competent pilot and was soon flying over the Mersey, where the surprised captains of Atlantic liners sounded their sirens in greeting.

By the end of the year, Freshfield had five aircraft. As well as Higginbotham’s Bleriot and Paterson’s Curtiss (soon to be superseded by another biplane with a 50 h.p. Gnome engine), other planes were flown by W. P. Thompson, a patent agent and the chairman of the Liverpool Aeronautical Society, and by Paterson’s pupil, R. A. King, of Neston; King’s plane, which was also a single-seater Bleriot, belonged to Henry Melly, who was the fifth of the Freshfield pioneers and who was to become Lancashire’s first fulltime flying instructor.

Thompson’s machine, which had two eight foot propellers and a 60 h.p. engine, included parts from an earlier biplane built for him by Handley Page. For the new venture, he chose the name Planes Ltd., and brought with him as engineer and pilot Robert Fenwick, who made at least one flight to Southport before the end of the year. King’s first flights – some over the sea, according to the Formby Times – were on Paterson’s Curtiss. The experience so captivated the young man that he ordered the latest 50 h.p. Farman from France. It arrived on Saturday, 26th November; and on the following Monday was tested by Paterson, by now the makers’ agent in the North of England, with King as passenger.’ The biplane performed its first two flights in such a perfect manner, reported the Formby Times, as to call forth loud cheers from the spectators … This machine places Freshfield well to the front in aviation. That evening, the two airmen and their friends held a celebration dinner at the Grapes Hotel, and made the headlines the next day by flying to Hoylake and back. The start was made shortly before two o’clock, and New Brighton was reached in a few minutes, said the Daily Post, pointing out that King was the first aeroplane passenger to be ferried over the Mersey.

The memorable day was by no means over. To loud cheers, Paterson flew to Freshfield, where he made two flights with passengers. One of them almost ended in the first aerial collision as Paterson flew within a hundred feet of Thompson’s biplane which was taking off below and which Fenwick hurriedly returned to the ground, causing serious damage. There were threats of litigation, but nothing seems to have come of them. Later in the afternoon, Paterson piloted his own plane to New Brighton, where had had arranged to meet a Daily Post reporter in order to describe the day’s events.

Henry Greg Melly was a 42-year old electrical engineer from Aigburth. He arrived in August, 1910 after spending his honeymoon in France, where he received his pilot’s certificate after nine weeks’ instruction at the Bleriot School in Pau. On 10th October, Melly became the third aviator to visit Southport, where he landed on the south side of the pier. When he repeated the flight a month later, he was joined by Fenwick piloting Thompson’s biplane. Though Melly remained a familiar figure at Freshfield, he moved his base to Waterloo at the beginning of 1911 in order to set up the Liverpool Aviation School. Four years before his death in 1957, he said of his days at Freshfield I flew a Bleriot single-seater – a copy of the plane in which the famous captain crossed the English Channel. It was powered by a 25 h.p. engine. In this I flew on occasions to Southport for breakfast. I used to park the plane under the pier. At Freshfield the hangars faced inland, and often we had to clear away sand which piled in front of them. We were frequently helped in this task by enthusiastic schoolboys from Formby.

Grahame-White was at Freshfield again in February, 1911, the attraction this time being his close friend, the American actress Pauline Chase, who was playing Peter Pan in a Southport pantomime. The two went up on 12th February and were closely followed by Paterson and a Miss Barnes from Freshfield. The engines were put on top speeds and something like a flying race was seen,’ said the Chronicle. The two pilots covered about eight miles, going as far as the Birkdale boundary and then returning to the hangars.

Between his visits to Freshfield, Grahame-White had had made a triumphant visit to the United States, winning more than £6,400 at the Boston-Harvard Aviation Meeting, and, on l4h October, 1910, astounding the whole country by landing his large Farman biplane in Executive Avenue, Washington, in order to pay his respects to a group of senior Army and Navy officers. It was the first time an aeroplane had landed in the streets of any city in the world. Grahame-White was planning to repeat the exploit on 18th February by delivering Miss Chase to the Southport Opera House when a call to the War Office, which was paying close attention to this development, upset his arrangements. On 5th March, 1911, Paterson and King again flew to New Brighton, where they circled the flagstaff on the Tower. They reached a height of almost 2,000 feet and travelled at about 45 m.p.h. In the following week, with Higginbotham, as his passenger, Paterson made a flight on his own machine lasting an hour.

In 1909 Sir William Hartley, Higginbotham’s father in law, had offered £1,000 to the first airman to make a non-stop flight between Liverpool and Manchester but by the following year the challenge of an attempt at a non-stop flight between the two cities remained. Encouraged by his long flight, Paterson, on Thursday, 16th March, decided to set out in King’s biplane and with King as his passenger to win this prize.

The airmen started from Freshfield in the direction of Hightown, reported the Chronicle, and made several attempts to reach a high altitude before cutting across country towards Cottonopolis; but owing to air currents, Mr. Paterson could not get the machine to ascend to the height he wanted – over a thousand feet – and on two or three occasions he had the greatest difficulty in keeping the Farman evenly balanced. When about a mile to the south-west of Formby Station, the machine, which was then about two hundred feet above the ground, was suddenly caught in a down current and was almost dashed to earth. In the descent, Mr. Paterson had the greatest difficulty in steering the aeroplane clear of some telegraph wires, and both aviators experienced a nasty sensation. The machine landed on rather rough ground with a shock, and as a result, the running gear was damaged rather badly. The mishap did not deter the airman, both of whom were to make flying their careers…….

King became a competent pilot and made numerous cross-country flights from Freshfield before taking a post with the Admiralty Flying School in 1913. On the evening of 16th May, 1912, with F. O. Topham as his passenger, he flew to Blackpool where he circled the Tower before landing on the sands opposite the Imperial Hotel. After dining there, the two men flew back to Freshfield, passing over Lord Street, Southport. On the following day the aviators abandoned an attempt to fly round the Liver Building in Liverpool when a thunderstorm forced them to descend rapidly at Egremont. King flew to Colwyn Bay and back on 7th June; and three days later Higginbotham, who had acquired Paterson’s biplane, reached Blackpool, where he spent an hour on South Shore.

Freshfield was now one of the most active flying centres in the country; and though crashes were frequent, injuries were rare. Higginbotham suffered most, losing part of an ear when his plan came down in the sea off Freshfield on 4th August. He and his mechanic swam ashore. Mr. Higginbotham, said Flight, did not appear to be upset in the least, and seemed as fearless in aviation as he used to be in motor races, smiling and remarking, “One must be prepared for upsets in new ventures of this kind”. On 13th and 14th October, Higginbotham flew from Freshfield to Southport with bags of mail. It was the first aerial post in the North of England and was prompted by the Hendon to Windsor service organised in the previous month by Grahame-White to mark the Coronation of King George V and to raise money for a hospital bed. Higginbotham carried forty letters and postcards on his first trip, and fifty on his second.

Towards the end of 1911, a new monoplane with its engine in the nose and its propeller behind the pilot flew for the first time at Freshfield. It was the brainchild of Fenwick and Sydney Swaby, an engineer with a special interest in power units. Thompson may also have helped to design this essentially military aircraft, which not only gave the pilot an unrestricted view, but also provided the space for a forward-firing gun. Trials are being kept as secret as possible’ reported Flight on 3rd February, 1912, but as the year went on, the monoplane was seen frequently over Merseyside, and on one occasion outpaced Higginbotham’s biplane when the two men raced over the shore. Fenwick and Swaby became licensees of Planes Ltd., and as directors of the Mersey Aeroplane Company, set about developing their novel machine. Henry Melly and his pupils, Lawrence Hardman and Edward Birch, were much impressed by the aircraft’s speed – 70 m.p.h. on occasions – and its stability when they flew as passengers. By the summer of 1912, the Mersey Monoplane had logged more than 700 miles without serious mishap; and when Fenwick landed on Southport sands on 29th May, he provided, according to the Visiter, a greater attraction than many amusements on the fairground. A week later, Fenwick, with Swaby as his passenger, repeated the visit, ruining a political meeting as audience and reporters abandoned politics for aviation. With an eye to a War Office contract, Fenwick and Swaby entered the Mersey Monoplane for the Military Trials on Salisbury Plain. There, on 13th August, Fenwick found himself in trouble after flying about a mile and a half. Almost immediately, the plane fell to the ground from 300 feet. Fenwick died among the wreckage. The official report found fault with the plane’s construction. It is possible, however, that a sudden gust of wind, which almost capsized another aircraft, was the cause of the disaster. Fenwick was not wearing a seat belt; the other pilot who survived

In 1910, Freshfield was a leading centre for five of Britain’s pioneer aviators, one third of those then flying in the UK. One of these, Cecil Compton Paterson, a motor engineer and company director from Liverpool, had an overriding ambition – not only to own a biplane based on the design of the American, Glenn Curtiss, but add some improvements of his own. His Liverpool Motor House Company then spent more than eight months building a machine, which, in the absence of any other suitable level open spaces, was duly tested on the sands at Freshfield, on Saturday, 14th May, 1910.